May 25

2013

Asthma plagues Peace Bridge neighborhood

D’Youville Porter School is a few blocks from the Peace Bridge.

Some 660 students attend the elementary school. A quarter have asthma.

Instruction at the school includes reading, writing and, for some pupils, how to use an inhaler.

“It is very difficult for these kids who are having asthma problems,” said Assunta Ventresca, director of health related services for Buffalo schools.

Asthma is an epidemic on the Lower West Side.

The victims, sometimes wheezing and struggling for breath, are in one in of every three households.

Studies found asthma rates are nearly four times the national average in the neighborhoods that share their air with the Peace Bridge and the 6 million cars, trucks and buses that cross it annually. The vehicles, especially diesel trucks, spew fumes that are known to worsen asthma symptoms.

“It’s the volume and the accumulative effect,” said Judith Enck, the Environmental Protection Agency’s ranking administrator in the Northeast. “The volume is what affects the air quality, and at the Peace Bridge there is a large volume of vehicles.”

Politicians have long pushed for bridge improvements to relieve bridge congestion and promote commerce.

And the toll barrier that frequently created big backups of trucks on this side of the border was moved from the U.S. to the Canadian side of the bridge in 2005.

Meanwhile, state bureaucrats in September 2012 released an unsigned report that downplayed the relation between bridge traffic fumes and the high asthma rates.

But an Investigative Post analysis of data and scientific studies found a strong body of evidence linking bridge traffic pollution with high asthma rates and other respiratory ailments among Lower West Side residents.

One study found that emergency room and hospital admissions for respiratory problems dropped dramatically when bridge traffic did after the 9-11 attacks and increased when traffic picked up.

Another study found airborne toxins, including those linked to agitating asthma symptoms, were most heavily concentrated in and around the bridge.

A third determined that asthma rates increased closer to the bridge.

The four most comprensive studies, and the most recent, were done between the mid-1990s and 2005, all in association with the same researcher.

“A lot of people are just ignoring the fact that you’ve got all these trucks and vehicles constantly congesting the place. The fumes from an exhaust are very, very horrible,” said Junior Vidal, a West Side resident whose wife and step-daughter have asthma.

Dr. Myron Glick, CEO of Jericho Road Family Practice and one of two Lower West Side private practices, also knows firsthand the toll of asthma.

“We have definitely seen, kids especially, sometimes teenagers, sometimes young adults, who are having such trouble breathing that the only treatment right now is to put a breathing tube down into their throat to breathe for them,” he said.

Ron Rienas, general manager of the Public Bridge Authority that operates the Peace Bridge, refused to comment about the impact of bridge fumes on public health. But in previous interviews, he has noted tougher EPA standards for diesel trucks.

Such vehicles built since 2007 are equipped with filters that are designed to remove 70 to 90 percent of harmful emissions. However, the EPA estimates older, dirtier trucks won’t all be off the road for another 17 years.

The white paper estimates that the new standards have already cut pollution from trucks by 50 percent, but it has no scientific study to back up that claim.

‘Thick smoke’ permeates neighborhood

The neighborhood around the bridge is one of the poorest and diverse in the city.

Some 15,800 residents live in the four Census tracts closest to the bridge. About one-third are Hispanic, another third white. Most of the balance are black or immigrants, many Somalis, Ethiopians, Burmese and Cambodians.

Poverty is pervasive. Nearly half of the residents live below the poverty line, including two-thirds of children. The median income in one Census tract was the lowest in all of Erie and Niagara counties.

An average of 13,000 cars and 3,500 trucks cross the bridge daily, making it the second-busiest crossing between Canada and the United States. Trucks idle on the bridge, in the U.S. plaza waiting for secondary inspections and at the Duty Free store parking lot that abuts the neighborhood. A strong odor of vehicle fumes at the U.S. plaza permeates the air on some days.

The volume of traffic is a health problem because an EPA report from 2002 concluded that breathing diesel fuel emissions can exacerbate asthma and other respiratory illnesses and cause lung cancer.

Madelyn Crespo, 40, and her three boys live a stone’s throw from the bridge complex. She never had asthma until she moved to the Lower West Side and all three of her sons were born there and developed respiratory illnesses. Crespo and her 6-year-old have had to visit emergency rooms six times for their asthma.

“It is pretty scary. We are talking about having to open up your child’s airway to breathe by giving him the treatment and sometimes that doesn’t even work right away,” Crespo said.

She made the connection between bridge traffic fumes and her family’s asthma after talking with other “hacking and coughing” neighbors and taking note of all the heavy truck traffic.

“A lot of big rigs come through here and those big rigs have those pipes that blow out that thick smoke,” she said.

Vidal, the other West Side resident, said he sees the link between his family’s asthma and living close to the bridge.

“The asthma started acting up a lot more when we moved closer to the Peace Bridge,” he said.

Studies link bridge traffic and asthma

Jamson Lwebuga-Mukasa, then an associate professor of medicine at University at Buffalo, discovered an unusually high number of hospital admissions for asthma almost 20 years ago on east and west sides of Buffalo. The pulmonologist and epidemiologist set out to find out why with a team of researchers.

One study reviewed bridge commercial traffic volumes, hospital discharges for asthma and outpatient visits before and after the North American Free Trade Act. The results suggested that an increase in commercial traffic had a negative impact on asthma sufferers who live near the bridge.

Researchers took this study a step further in an effort to determine whether decreases in bridge traffic following the 9-11 terrorist attacks resulted in fewer hospital admissions and emergency department visits for respiratory illnesses by West Side residents. The study found that when traffic dropped, so did the number of respiratory cases, by as much as 75 percent from the previous year. They concluded that bridge traffic levels may be impacting the respiratory health of nearby residents.

In 2002, Mukasa led a different study that found 37 percent of West Side households had at least one person with asthma, which is roughly four times the national average. The survey found 46 percent of households reported at least one case of chronic respiratory illness.

The East Side also has high asthma rates, but the study found that the odds of having at least one person with asthma in a home was 2.57 times higher on the West Side, even when correcting for race, socioeconomics and six household triggers.

Mukasa’s team monitored the air in 2001-02 and found concentrations of airborne particles that can exacerbate asthma increased closer to the bridge. Researchers also documented more cases of asthma in neighborhoods closest to the bridge. Together, this led them to conclude that bridge traffic played a role in the high number of asthma cases near the bridge.

In 2004, Harvard University’s Health Effects Institute teamed up with Mukasa and other universities to monitor air quality along the waterfront and in the neighborhood abutting the bridge. They found high levels of air toxins when the wind was blowing from the bridge toward the neighborhood. Some of the pollutants reached as deep as six blocks into the neighborhood.

The researchers concluded the Peace Bridge area should be considered a toxic hot spot. But a peer review committee nixed that recommendation.

Its reasons: Pollution levels were not as high as in other cities such as Houston and Los Angeles, and are influenced by wind direction, suggesting that nearby Thruway traffic could be a contributing factor.

“While the bridge is a big, obvious source that could be contributing to the neighborhood, there are other sources,” said Dan Greenbaum, president of HEI.

Mukasa said state bureaucrats should not downplay the role bridge traffic has on asthma in the Lower West Side.

“In the immediate area the bridge traffic contributes significantly to the asthma,” Mukasa said.

Data points to problems

An Investigative Post analysis of state Health Department data for 2008-2010 shows West Side residents are discharged from hospitals with an asthma diagnosis or treated in emergency rooms for asthma at a rate more than double the national average. The rate of West Side children discharged from a hospital for asthma is more than three times the national average.

Dr. Raul Vazquez of Urban Family Practice on Niagara Street said he has seen about 5,000 patients with respiratory conditions, more than half from the Lower West Side. His office prescribes roughly $800,000 annually in respiratory medications, which is the most in Western New York for a primary care physician.

A pharmacist, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said employees compared rescue inhaler sales from a West Side pharmacy to a comparable drug store on the East Side.

“The use of rescue inhalers at the West Side pharmacy was four times greater than the one on the East Side for that month,” the pharmacist said. “It was an eye opener, for sure.”

The West Side drug store, one of several in the neighborhood, sells some 9,000 inhalers annually.

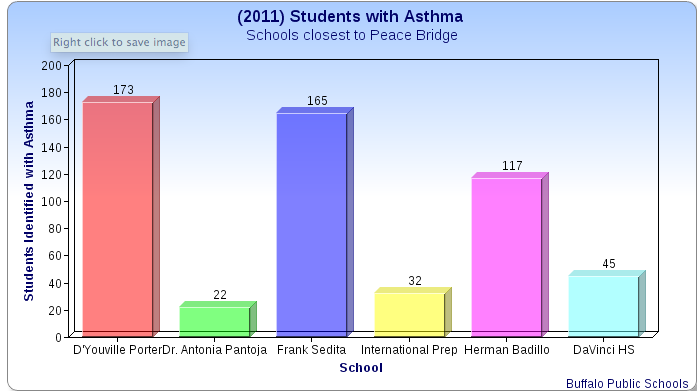

Buffalo school officials concerned about the proposed bridge plaza expansion plans informed the Public Bridge Authority and federal transportation officials in 2009 that at least 544 students attending West Side schools had asthma. That number has since increased by 10, in part because of a 16 percent increase at D’Youville Porter School.

Other factors also at play

The state’s white paper report attributes smoking, pollen, housing conditions, poverty and race – rather than bridge traffic fumes – as major contributors to the high asthma rates.

“Since most people are typically exposed to a wide range of asthma triggers (including colds/flu, stress, dust mites, pollen and others), the relative contribution of traffic in the development or exacerbation of asthma within a particular individual or community is uncertain,” the white paper states.

Scientists working with community organizations have disputed the paper’s conclusions.

“All this report did was cherry pick things from certain studies that support a particular conclusion,” said Joseph Gardella, professor of chemistry at University at Buffalo and chairman of the city’s Environmental Management Commission.

State officials in three agencies, when pressed to explain and defend their report, declined to do so. They rejected five interview requests from Investigative Post.

Jacob McDonald, a director for Lovelace Respiratory Research Center in Albuquerque, N.M., thinks improved air quality is inevitable, especially since the new filters were installed on diesel trucks in 2007.

“Arguably, the changes that the diesel industry made to meet those standards in 2007 should have a substantial benefit to the community in terms of a health because they made a very significant change in the potential exposure that is going to occur,” he said.

Investigative Post determined other problems as well: few doctors on the Lower West Side to treat asthma, and the absence of a coordinated effort to address health-related issues.

Census data shows that there are 11 doctor offices for the two ZIP Codes closest to the bridge—only two in the Lower West Side—for about 36,000 people. In contrast, there are 280 offices in Amherst for 122,000 people.

“You need more people engaged who really want to solve the problem,” Vazquez said. “The services may be there but they are so fragmented.”