Dec 20

2012

The Great Lakes are stressing out

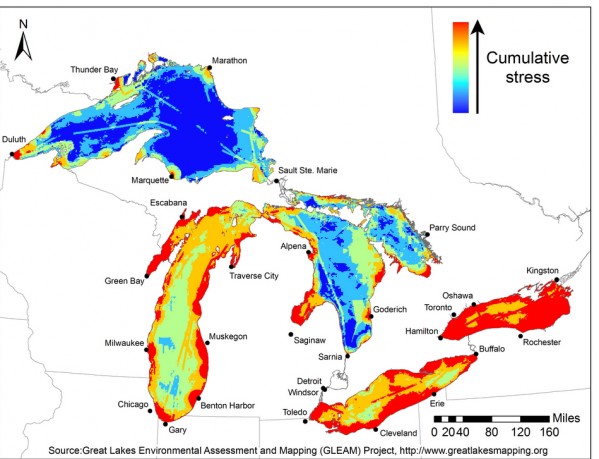

This map shows a sea of red off of Buffalo and many other Rust Belt cities where environmental stressors are harming the nation’s largest fresh water source, the Great Lakes.

People can heed the data and maps as a warning — the red doesn’t mean death, but it helps point people to where the focus needs to be to reverse the impacts of these environmental stressors, said the chief researcher for the project, J. David Allen, a professor of aquatic sciences at the University of Michigan’s School of Natural Resources and Environment.

Other Great Lakes experts might argue that the places in red are contributing more to what they consider to be a tipping point of the resiliency of the fresh water source.

You can read about the approach and methodology of the work here.

“What we have is a system that is clearly under stress, that some people have likened to death by a thousand cuts,” Allen said during an interview with Investigative Post on Wednesday afternoon.

The map above illustrates the combined effect of 34 stressors, broken out into seven categories that include climate change, invasive species, toxic chemical pollution and coastal development. Researchers surveyed Great Lakes experts to rank the importance of each stressor. For example, Allen said experts thought the invasive species Zebra mussel and sea lampreys, climate change variables and coastal development posed the biggest threats, while lake pollution was less of a concern.

“The redder places just have more different kinds of human influences,” Allen said. “If you have a city in a river mouth, you’ve kind of got a collection of human activities that in their summation have a greater influence. If you are along the coast you are more likely to be red because you’re influenced by both land-based stressors and water-based stressors.”

The round goby is an aggressive bottom-dwelling species that spawns several times each season and can dominate the waters. They prey on eggs of other fish.

“They are just incredibly abundant, particularly in Lake Erie,” Allen said. “Our survey experts kind of put it somewhere in the middle of the road. They didn’t say round goby is as bad as sea lampreys or as Zebra mussel, but they had it up there in the upper half.”

Zebra and quagga mussels have numerous impacts on the Great Lakes — to put it bluntly, these are some ugly invaders.

There’s a nitrogen load problem that drives algal growth and causes the water to overload in organic and mineral nutrients that increase plant life at the expense of animal life.

Copper, Mercury and PCBs also pose a threat.

Are the Great Lakes dying? Not tomorrow. Not next week, next month or next year. But the sheer number of stressors that impact the Great Lakes is eye opening nonetheless — a warning, as Allen put it.

Allen pointed out that the value of the index is, for the most part, in the low to mid range — in other words, not red but more like blue or light blue.

“I’d like to emphasize that in that respect the glass is at least half full,” Allen said. “The Great Lakes are still a very healthy ecosystem and Lake Erie is a wonderful fishery, yet at the same time we see all of these things happening. So you can’t say the lakes are dying or the lakes are terrible and you can’t say everything is OK.”

Jay Burney, founder of GreenWatch and the Learning Sustainability Campaign in Buffalo, said one of the exciting aspects of this project is it marks the beginning of a process to better understand the cumulative factors of all of the stressors to the Great Lakes ecosystem.

“Cumulative factors link such issues as climate change, sewer overflows and urban pollution, agricultural runoff, habitat alterations, development, fisheries, biodiversity, invasive species and a host of other things that contribute to what can be described as the collapsing ecosystems in the Great Lakes and in the Great Lakes watersheds,” he said.

“This work is important and can be used as a tool to inform our critical sustainability decision making throughout the Great Lakes, and in Buffalo and Western New York. This is very important work.”