Sep 19

2016

SUNY Poly plays by the rules — or, guidelines

Editor’s note: A version of this story published Sunday in the Times Union of Albany.

Two state-affiliated development corporations at the center of a federal corruption probe operated for years without rules commonly used by government agencies to promote competition, discourage favoritism and get the best deal for taxpayers when choosing companies to do business with.

As a result, they’ve used unusually loose procurement policies to select developers for multimillion dollar projects, an Investigative Post analysis shows. Some of their contract awards – often to Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s major campaign donors – are now being investigated by state and federal prosecutors.

The Fort Schuyler and Fuller Road Management Corporations, which act as the real estate arms of the SUNY Polytechnic Institute, administer many of Cuomo’s most ambitious initiatives to boost the upstate economy, from the vast solar panel factory nearing completion in Buffalo, to high-tech hubs in Albany, Utica, Syracuse and Rochester.

The development corporations say they follow the procurement policies of their parent organization, the Research Foundation for the State University of New York – but only as “guidelines.” And, in fact, the way they do business is sometimes out of step with the procurement practices of the Research Foundation and other state entities.

The development corporations have often failed, for instance, to ensure the minimum level of competition the Research Foundation requires. In at least three cases the development corporations awarded contracts to companies who were the lone bidder. In Syracuse, for example, COR Development faced no competition when the company submitted a proposal to become Fort Schuyler’s go-to developer in the region.

Moreover, the development corporations have given contracts to developers who rank among Cuomo’s largest campaign contributors, sometimes in ways that have raised questions about whether bid specifications were written to favor certain companies.

In Buffalo, a requirement that developers have at least 50 years’ experience in the market seemed to limit the field to just one company, LPCiminelli, whose owner is a major donor to the governor. That requirement was later changed to 15 years, with officials explaining it as a “clerical error”. LPCiminelli got the job anyway.

“The absence of a procurement policy that’s robust and written in a way that ensures fair bidding is a huge problem,” said John Kaehny, executive director of good government group Reinvent Albany.

Investigative Post’s review of over 500 pages of records obtained from the development corporations under the state Freedom of Information Law found a lack of consistency in the way Fort Schuyler and Fuller Road advertised and awarded lucrative contracts to developers.

Sometimes, the selection process was clearly competitive, with a detailed evaluation of a number of firms who had submitted proposals. On other projects, officials were choosing from only a handful of companies – or, in several cases, just one.

Officials from SUNY Poly refused to respond to repeated requests for comment. David Doyle, the college’s vice president for public policy, has previously said that SUNY Poly and its affiliated development corporations “follow New York state government’s well-established and legally defined procurement procedures – to the letter.”

But a lawyer for the development corporations appeared to contradict this, saying in response to an FOI request from Investigative Post that Fort Schuyler and Fuller Road “utilize the procurement policies promulgated by the Research Foundation for the State University of New York as guidelines.”

The development corporations have made changes to their procurement practices over the past year and now behave more like state agencies. But these changes come only after they have found themselves at the center of state and federal investigations into potential bid-rigging and improper lobbying – and after much of the money allocated for major projects had already been spent.

“As guidelines”

For years, Fort Schuyler and Fuller Road have spent public money while insisting that they are private nonprofits and, therefore, exempt from state Freedom of Information and Open Meetings laws.

Control over construction work worth hundreds of millions of dollars gives the development corporations immense power with limited oversight compared to state agencies. The state comptroller’s office, for example, does not review or approve their contracting.

The development corporations were created as nonprofits to get around state and federal rules SUNY Poly says prohibit the state university system from leasing space to private companies. The development corporations equip and lease these high-tech facilities to private companies like General Electric and IBM, who invest in research and development and create hundreds of new jobs.

Fuller Road was created in 1996 by foundations associated with the SUNY system and oversaw the construction of SUNY Poly’s vast NanoTech complex in Albany. Its younger sister, Fort Schuyler, was established in 2009.

The development corporations expanded their reach across upstate after Cuomo took office in 2011.

SUNY Poly’s founding president, Alain Kaloyeros, has become Gov. Cuomo’s point person on many of the state’s largest economic development projects. Fort Schuyler has been administering state funds for the Buffalo Billion initiative, as well as for projects in Syracuse, Utica, and Rochester. Fuller Road has been performing a similar role for projects in the Capital Region.

Both development corporations say they follow the SUNY Research Foundation’s procurement policies only “as guidelines,” and it’s clear they sometimes depart from those guidelines.

The Research Foundation’s procurement policy requires at least three written bids or proposals for any contract worth more than $100,000. Fort Schuyler and Fuller Road have failed to establish this minimum level of competition on some far larger contracts.

After advertising for a “preferred developer” for projects in the Rochester area, for instance, Fuller Road received just two proposals – and awarded both firms the contract. Instead of covering just one project, the preferred developer contracts are open-ended, potentially involving additional work the development corporations carry out in the region for up to 10 years.

In Albany, another preferred developer contract went to yet another major Cuomo donor, Columbia Development, whose president, Joseph Nicolla, and LLCs connected to the company have given the governor at least $210,000 over the past six years. Columbia was the only firm to express interest in that contract, much less submit a complete proposal. Documents suggest that Columbia has only received a relatively small amount of work under this contract so far.

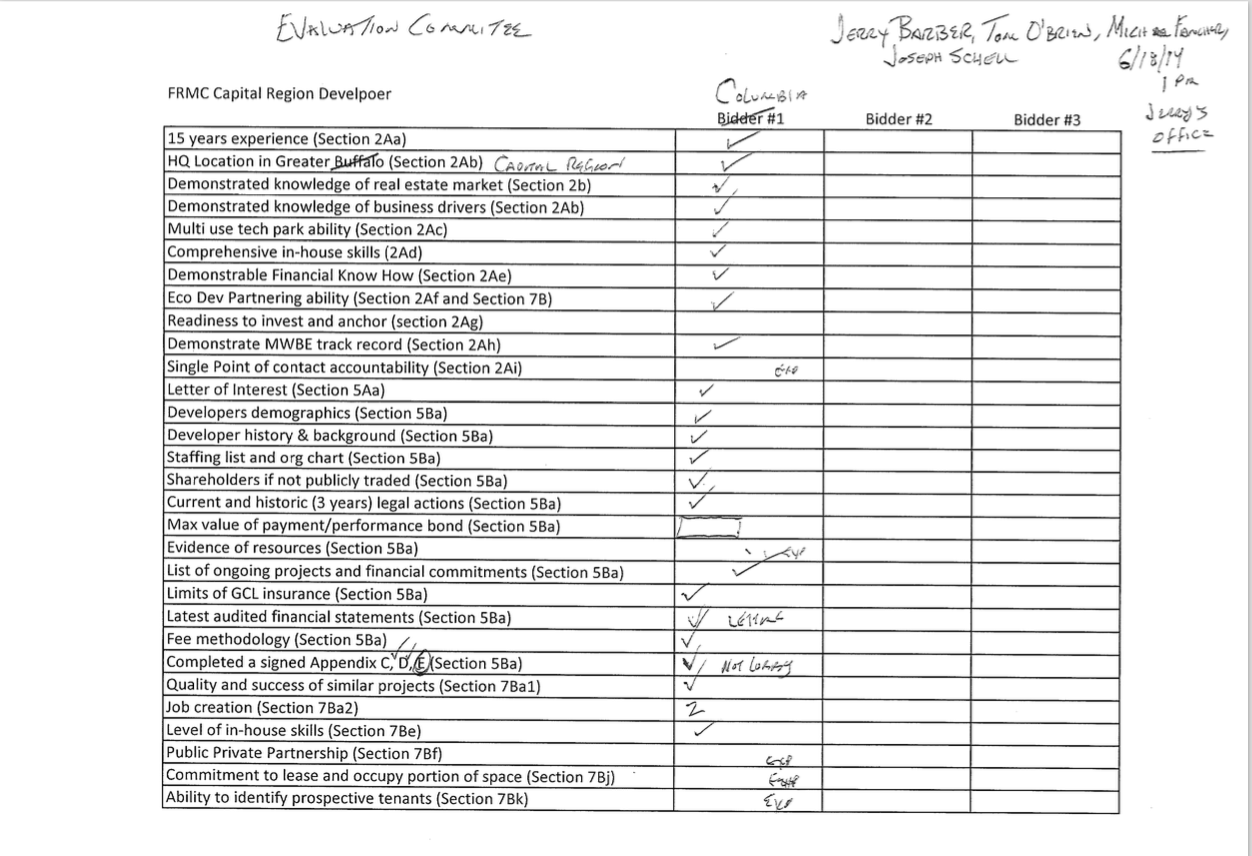

Used by FRMC to evaluate companies for a preferred developer contract in the Capital Region.

A year later, when Columbia was again the only company to respond to a request for proposals to build student housing, Fuller Road once again awarded them the contract. The RFP included a preference for a site within a 10-minute walk of SUNY Poly’s campus. As the Times Union reported, Columbia had been buying up property in the area months before the request for proposals went out.

The project was later rebid, with eight firms submitting proposals and the “walking distance” preference removed; the original selection process is currently the subject of an investigation into potential bid-rigging by state Attorney General Eric Schneiderman.

Like other contracts for professional services, these developer contracts aren’t simply awarded to the lowest bidder; a company’s past experience, qualifications and track record are also taken into account.

Best practices still call for a competitive selection process, though. Instead of soliciting proposals from a wide range of companies, however, the development corporations appear to have done little to encourage competition for work on major projects.

Advertisements were typically placed in the legal notices of local newspapers, but not on the state’s centralized procurement website or sent to potential candidates directly, as is more usual for major public contracts.

Two contracts for work on Fort Schuyler’s Central New York Hub, a $15 million film production facility currently sitting empty, illustrate the effect of these nebulous procurement rules.

The first, a lucrative “preferred developer” contract, was advertised three times over six days in October 2013, in a legal notice in the Syracuse Post-Standard.

Four companies expressed interest, but only one, COR Development, actually submitted a proposal. The company’s principals have given Cuomo at least $340,000 since 2010.

Other area firms later told the Post-Standard they had not been aware of the opportunity, but had they been, said they would likely have submitted proposals.

“That’s a heck of a deal,” Michael P. Falcone, chairman and CEO of Pioneer Companies, another prominent developer in the region, told the newspaper. “I kind of wish I had seen that ad.”

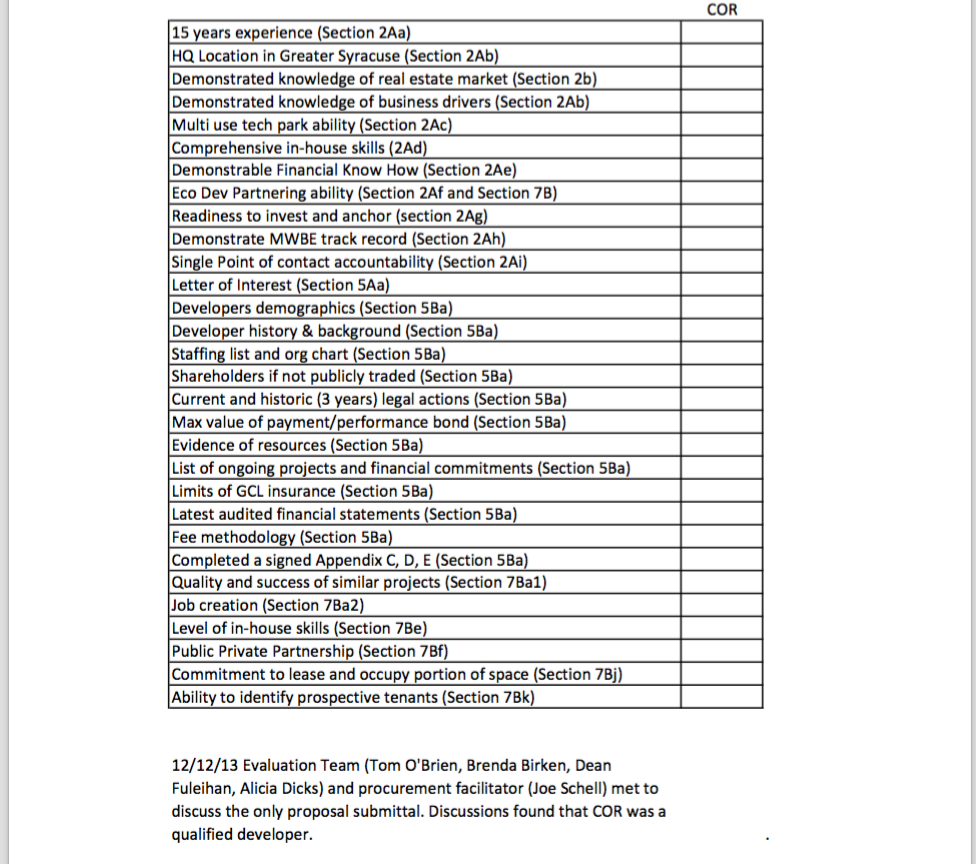

Fort Schuyler officials drew up a grid to evaluate proposals, but left it blank: there were no other companies to rank the lone bidder against. They simply noted, “discussions found that COR was a qualified developer.”

FSMC evaluation document for Syracuse region preferred developer contract.

The company had close ties with two men now at the center of U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara’s investigation into the Cuomo administration’s economic development efforts: lobbyist Todd Howe and former top Cuomo aide Joseph Percoco. The latter reported receiving at least $50,000 in consulting fees from COR on his 2014 financial disclosure form while on leave from state government to run the governor’s re-election campaign. COR has denied paying Percoco.

A much smaller contract to supply office furniture for the film hub built by COR, worth less than two hundred thousand dollars, attracted interest from twelve companies after being advertised more widely.

By contrast, COR’s preferred developer contract could be worth millions of dollars. As well as the $15 million film hub, the company is building a $90 million factory for high-efficiency light bulb manufacturer Soraa – and any other projects Fort Schuyler carries out in the Greater Syracuse area as part of a deal that could run for as long as 10 years.

Mismatch of needs

SUNY Poly says using the nonprofits is “required by federal and state rules, including IRS rules that prohibit hosting private corporations on state-owned lands.”

Critics say SUNY Poly has used their status as private nonprofits to skirt state transparency and procurement rules.

“When they were created as the children of the SUNY Research Foundation, they chose not to adopt the exact same practices and procedures – there’s a reason for that,” said Kaehny, of Reinvent Albany.

When Investigative Post and WGRZ-TV asked Fort Schuyler for documents under the FOI law relating to the selection of developers in Buffalo in 2015, officials argued that, as a private nonprofit, it wasn’t subject to the law. It took the filing of a lawsuit by the two news organizations for Fort Schuyler to release the records on its website.

Moreover, the Research Foundation’s procurement policies don’t align particularly closely with the development corporations’ needs.

Where Fort Schuyler and Fuller Road administer massive construction projects, the Research Foundation buys mostly professional services, software, and research supplies.

For construction work, the Foundation relies on the SUNY Construction Fund, which has more stringent rules to encourage competition, requiring that officials choose from a shortlist of at least five proposals for any contract over $300,000.

And whereas the Research Foundation does not require that contracting opportunities be advertised in the State Contract Reporter, the Construction Fund advertises all its contracts there, regardless of size, as well as on its own website.

Since last fall, Fort Schuyler and Fuller Road have been advertising procurement opportunities more widely, including in the State Contract Reporter.

While soliciting proposals for the projects in Syracuse and Buffalo in 2013 and much of 2014, however, Fort Schuyler’s one-page website didn’t include any contact information, much less bid specifics. Fuller Road only unveiled its website earlier this summer.

“Rebranding” policies

At Fuller Road’s most recent meeting, board members scrambled to praise the transparency and fairness of the corporation’s procurement practices. It was the first of Fuller Road’s meetings to be open to the public, after a request from reporters at Gannett’s Albany bureau pointed out that the development corporation had been doing business in private. Fort Schuyler has opened its meetings, too.

Board members were anxious to stress that the selection of developers for SUNY Poly’s student housing, the second time round, was done by the book.

Just a few months earlier, however, with the ongoing federal and state investigations placing Fort Schuyler and Fuller Road under increased scrutiny, board members at both development corporations had been raising their own concerns about the entities’ procurement rules.

At a Fuller Road meeting in January, one board member said that, as part of developing a long-term plan, the corporation should “adopt a clear procurement process.”

A month later, Fuller Road’s president Walter Barber, who has since retired, told board members that the corporation’s auditors had recommended that they document their procurement practices more thoroughly.

The corporation’s management later agreed to “rebrand” the Research Foundation’s policy into a draft, written policy for Fuller Road.

Records obtained by Investigative Post, however, did not indicate that Fuller Road and Fort Schuyler had adopted written policies as of the end of June.

Some board members have also questioned whether the corporation should continue to use the “preferred developer” approach – unusual in the public sector – which effectively tamps down competition by awarding one company an open-ended contract rather than bidding individual projects separately.

SUNY Poly officials said earlier this year that the development corporations are moving towards awarding more contracts on a project-by-project basis.

But even as board members proclaim a new era of transparency, the development corporations won’t fully concede that they are bound by the same rules as state agencies.

After Fuller Road voted to open its meetings to the public, Barber said the nonprofit had chosen to “subject itself” to the Open Meetings law – not that it had any existing obligation to do so.

At the end of the August meeting, board members voted to go into executive session, “guided by” the section of the state Open Meetings law that allows public bodies to discuss investigations and pending litigation in private. Board member Michael Castellana wanted to check: “We’re quoting that law as a guideline to our behavior, not as a requirement for Fuller Road Management Corp., is that correct?”

Kempf, the corporation’s general counsel, confirmed: it’s just a guideline.